When Barbara’s world collapsed

Individuals who leave Christian Science tend to arrive, after some wandering, either at a commitment to the biblical Christianity from which CS originally departed or—more often, sadly—at an atheistic, agnostic, or self-generated spirituality that blithely disavows God. My heart goes out to these “nones,” as sociologists call them.

Because the spiritual void they attempt to maintain may eventually be filled with beliefs and attitudes more harmful to them, in time and eternity, than was the CS belief system they formerly held. As a result, in the words of Jesus’ parable, “The last state of that person is worse than the first” (Matthew 12:45).

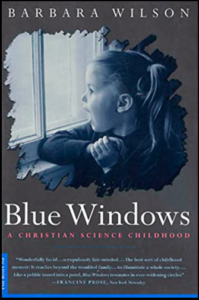

Such was my thought process recently in writing an article for our friends at the Fellowship of Former Christian Scientists about Barbara Wilson’s 1997 book, Blue Windows: A Christian Science Childhood.

“How can I, so harmed by this church, still find it the source of so much meaning in my life?” That’s the question this award-winning author and translator, firmly in the ranks of the “nones” as she nears fifty, sets out to explore in a dramatic memoir of her experiences up to about age 15.

As a story, I found it engaging and moving. As a venture in self-knowledge, I found it admirably discerning and honest. For any of us working to make sense of how Christian Science helped shape the person we became, Wilson’s powerful book deserves a place on our shelves—alongside Linda Kramer’s Perfect Peril, Lauren Hunter’s Leaving Christian Science, Lucia Greenhouse’s Father Mother God, and Caroline Fraser’s God’s Perfect Child. (And if your shelf also finds room for my book Discovering a Larger God, even better; I’d be grateful.)

Tragic

Blue Windows reads like a tragic novel, yet all the characters and events are real. Little Barbara is a bright, shy, sensitive tomboy growing up in California and Michigan in the 1950s. Bruce is her younger brother and sometime best pal. Ellen, their mother, is an earnest, class-taught Christian Scientist. Cecil, their father, starts as a mild agnostic but becomes a militant Lutheran. Grandma Faith Lane is a strong-willed, no-nonsense practitioner, matriarch of the family.

Uncle Andrew, Ellen’s brother, secretly molests Barbara and is later institutionalized with schizophrenia. When Cecil remarries after Ellen’s death, we meet Bettye, the coarse, cruel stepmother, and Mike, her worldly-wise teenage son.

Ellen Wilson’s harrowing three-year battle with mental illness and breast cancer, which claimed her life when Barbara was only 12, is the focal point of the book, both as a narrative and as an exploration of religious belief.

The young mother’s death, after worsening insanity and repeated suicide attempts—one of which horribly disfigured her face—not only shattered the daughter’s snug, sunlit world. It also disproved her rosy worldview, whereby faith in an all-good God was supposed to guarantee the faithful a happy life. Not any more, the disillusioned girl began to realize; and she was never the same again.

Rosy or Blue?

The blue windows of the book’s title allude to a children’s article in the Sentinel that had deeply impressed the precocious Barbara. They represent an outlook on life where sorrow, suffering, and struggle predominate, and which Christian Science teaches us to reject for a rose-window outlook where all is always well. Reality, though, is decidedly blue, she concludes in her grief.

Even so, breaking with the ingrained CS life-patterns takes Wilson several more years—which will sound familiar to many of us who have had to make that drawn-out transition—and the recurrrent nostalgia for Science’s simple, sweet, secure emotional cocoon persists with her for decades after that.

Intertwined with her personal story, Barbara Wilson gives us a well-researched, meticulously accurate, and skilfully constructed account of how Christian Science arrived on the American scene and how Mrs. Eddy obtained a huge following despite some of her unlovely traits. She finds things to admire as well as deplore in both the religion and its founder.

Wilson speculates on how CS may have contributed to her mother’s disease and death, yet refrains from casting blame. The whole book avoids a simplistic good guys vs. bad guys framework in regard to either individuals or institutions. Everyone had their reasons for acting as they did, she seems to say–and labels only obscure the understanding we all must strive for.

A Conversation over Coffee?

“Scrupulously fair-minded,” a New York reviewer called Blue Windows when it came out in 1997, and I warmly agree. Wilson comes across as a remarkable human being, someone I’d enjoy knowing, although we have little in common except being contemporaries in age and both raised in Christian Science—though in my case with none of her trauma.

Her eclectic spirituality (tinged with Buddhism), feminist preoccupations, left-liberal politics, and lesbian sexuality, touched upon in the later chapters, won’t be to every reader’s taste, but they glide past, never harped on. Subtle color accents on a perceptive self-portrait, one might call them. They are part of the introspection she distills from retrospection, shall we say—to play off the title of Eddy’s autobiography, where far less depth is achieved than here in Wilson’s.

I think if we could meet for coffee some time, I’d like to ask Barbara about her mid-teens experience of gradually “acknowledging that the all-loving, all-knowing, all-powerful, all-good God I had known as a child, did not exist.” It was to be a turning point, she adds, for “I knew that once I let go of this God, the god of my childhood, I would not be able to believe in another one.”

It’s the exact conclusion that many people, perhaps most people, who leave Christian Science settle upon. I know that very well. But I also know from my own experience, as you may know from yours, that it doesn’t have to be that way. The true and living God is still out there, waiting to welcome former Christian Scientists home as the adopted brothers and sisters of his crucified and resurrected Son, Jesus Christ.

Even now, after all these years, all the wandering paths you may have walked, He is there. He’s left the light on for you. Do you know that, Barbara Wilson? That’s what I’d like to ask the Blue Windows woman-child over coffee.

The author can be reached at andrewsjk@aol.com