Imperfect child: My debt to Caroline Fraser

“I alone have escaped to tell you.” This is the refrain, three times in the first chapter of the Book of Job, when wide-eyed survivors bring the old man ever-grimmer reports from the scene of tragedy. It has become a life verse for me since escaping Christian Science.

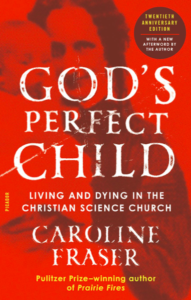

I’ve sought to testify, for others’ benefit, from firsthand experience of the tragic harms done by the Mary Baker Eddy belief system over the past 150 years in America and across the world. I am now better equipped to do that, as a result of the witness borne by journalist Caroline Fraser in her powerful book, God’s Perfect Child: Living and Dying in the Christian Science Church (Macmillan, 688 pages, 2019, $22.00).

Christian Science as a religious movement and way of life is a little world of its own—distinctly separate from, though embraced within, the ordinary world everyone else lives in. That separateness is enforced by CS having its own specialized vocabulary, its own sacred book effectively superseding the Bible, its own health code, and in particular its own tightly-policed index of impermissible thoughts, by which intellectual curiosity and doctrinal doubts are flatly forbidden.

The Eddy system thus becomes a self-reinforcing worldview, very difficult to step outside of at all, let alone completely discard and shake off. This where I found Fraser’s book so valuable. It gives the former Christian Scientist a vantage point from which to look back into that bubble we escaped from and see it whole—horizontally across its strange interior landscape and vertically through time.

An accomplished writer and researcher, formerly on the staff of The New Yorker, Caroline Fraser first sets the scene in her own happy Christian Science childhood (having turned away by age 20, one gathers, from CS and religion in general ). Then in voluminous and fully documented detail across more than 400 pages, she recounts Mrs. Eddy’s biography, the phenomenal growth of CS up to the founder’s death in 1910, the movement’s faltering momentum thereafter, CS setbacks after 1970, and efforts at reinventing itself as the year 2000 approached—where the book ends.

Thus we have in God’s Perfect Child both a history and a map. Fraser recognizably but rather neutrally depicts the oddities of “planet CS” as we’ve all lived them. She locates Christian Science beliefs within contemporary thought but wastes little time arguing with them.

She simply tries to follow the facts where they lead, taking—it seemed to me—as mild a tone and as fair-minded and honest a stance as she can, by no means friendly but not hostile either.

Cold Realism

Where the facts do lead, however, she concludes again and again (and I agree), is to a most unflattering picture of human credulity and the resulting harm done, now spanning more than two centuries since Mary Baker’s birth in 1821.

Were there good intentions, lives well lived, blessings received, situational improvements that one could call healings? In countless instances, yes, no doubt.

But at the same time, so many lies and delusions, so much self-seeking and greed, such dreamy self-deception and callous disregard of suffering—help, let me out of here! You mean to say I once believed this?

And that’s why I say, taking no pleasure in doing so, that this firehose of cold realism has been exactly the right book at the right time for my current need of post-CS spiritual growth. It leaves my often too-cozy rationalization of Christian Science as “not entirely good, granted, but not all that bad either,” with no place to hide.

Even 30 years after leaving the church, I still sometimes discern in myself a sort of gravitational pull to make excuses for CS denialism and the unnecessary hardship it has inflicted upon so many for so long. Within that bubble, after all, I did have some happy times, some cherished associations with family and friends, some exhilarating seasons of soldiering faithfully for what seemed a worthy cause.

When confronted with an unsparing critique of this or that aspect of Christian Science—unauthorized biographies of Mrs. Eddy, bleak statistics on CS healing claims, seamy insider accounts of Boston dysfunction—it was easier for me back then (and alarmingly, sometimes even now) to dismiss them as slanted, not quite fair, perhaps even godless and malicious, than to face them head on. The Fraser book, recounting the whole tangled story in one place, has helped me push past that.

A Task Postponed

There was a task of forgiveness I’ve been postponing for way too long. I needed to forgive my parents and their parents, my teachers at Principia, numberless practitioners and CSB’s, even Mrs. Eddy, I guess—and to forgive myself—for the monumental mass of falsehood and folly that was and is Christian Science.

I’ve clung, without realizing it, to various shiny objects, hoarded keepsakes, from the CS period of my life that seemed to confer upon me a sense of worthiness and significance which I was afraid to let go of. I must have feared that to flatly invalidate the entire Christian Science “thing” would be, at the same time, to invalidate myself in the bargain.

So while I could readily profess, with St. Paul, “I am crucified with Christ, nevertheless I live… they that are Christ’s have crucified the flesh with the affections and lusts” (Galatians 2:20 and 5:24), I was still doing so with my fingers crossed behind my back. I hadn’t stopped secretly deriving part of my identity from the solid, secure genealogy of the Andrews clan, born and bred to Eddyism.

I had bought God’s Perfect Child in 1998 when it first came out, browsed through parts of it, and put it aside. I took note of the book again several years ago when Caroline Fraser brought out a new edition with an afterword about her father’s agonizing death under Christian Science treatment. Only this year, however, in the summer of 2022, did I read the book in full—and it hit me hard.

I came away feeling somehow soiled and stained by the stew of illusions and lies that the CS movement has foisted on the world across the whole span of its presence in American life. I was filled with an odd, numbing emptiness where my “not that bad and in many ways pretty good” fallback position as an ex-CSer used to be. All of this, I now see, was God using the book to draw me nearer him—him alone.

If God’s forgiveness of my sins, through Jesus Christ crucified and risen, was as boundless as I professed to believe it was, then my religious past must be fully cleansed in his sight. His forgiveness of me is the basis for the forgiveness I want to extend upon myself and others. Even the unnecessary loss of a parent in their 50s, under CS “radical reliance,” something that befell both my wife and me, is forgivable under our gracious Father’s atonement in his Son. Even our undiminished hypnotic loyalty to CS after those tragedies is forgivable!

Cathartic

My experiences this year, showing me new horizons of total reliance on our triune God for my identity, worth, and purpose, are parallel to the deepening humility Paul gained as he did ministry and matured spiritually. In his letters, as if descending a stairway, he goes from calling himself an apostle, to asserting he’s unfit to be so called, to saying he’s less than the least of saints, to finally insisting he’s the chief of sinners (Gal. 1:1, I Cor. 15:9, Eph. 3:8, I Tim. 1:15).

I can relate, and my cathartic encounter with the Fraser book has been part of that needed process of self-reproach and cold reappraisal. As John the Baptist said of Jesus, “He must increase, but I must decrease” (John 3:30). We all must. Whatever elegant apparel of religiosity we once paraded in—in my case, the garb of an over-achieving Christian Scientist—must go in the rag bin before we can don the white robes Jesus offers us.

It has been wisely said that for the Christian, the opposite of faith is not doubt, rather it is self-reliance. Or self-salvation, as I have come to realize in escaping Christian Science. Caroline Fraser argues at the close of God’s Perfect Child that we should expect the damaging societal effects of CS to be persistent and widespread though unseen, even as the movement itself, the CS brand name, withers away—because “in American life, extreme self-reliance is here to stay.” And alas, she’s probably right. One more reason her book belongs on your shelf.

The author can be reached at andrewsjk@aol.com